Over Christmas, a family member asked me whether I like The Chosen or think there is a problem with it being “unbiblical.” That word again!

In this case, unbiblical refers to the addition of “extrabiblical” details, context, and exposition not found in the Gospels and, generally, the rendition of the story with artistic license. In addition to the fact that every sermon on a Gospel text inevitably does this—otherwise we would be left with nothing more than reciting the text—I appreciate creative representation of the life of Jesus. If you don’t appreciate it, then stop doing live Nativities at your Christmas services. Actually, even if you do appreciate it, please stop doing Christmas pageants anyway. Not because they get the story wrong—and every one I’ve ever seen did get the story wrong—but because they’re painful to sit through. Thanks.

I love The Chosen. I’ve dreamed about what a well-made cinematic version of the gospel story would look like since high school. I can scarcely imagine a better fulfillment of my hopes for a careful, insightful, creative depiction. When I watch it, I have a feeling of recognition. It hits notes that I’m familiar with as a student of the Gospels.

So, no, I don’t care that it’s “unbiblical.” Why would I be? It’s not the Bible. It’s not trying to be. Go read the Bible if you want strictly “biblical.” It’s still there after every season of The Chosen airs.

But recently, I came across another criticism of the series (thanks, TikTok). Pastor and influencer Voddie Baucham claimed on an episode of The Babylon Bee Podcast that The Chosen is a “2CV” (Second Commandment violation), namely, “portraying Jesus as idolatry.”

Ordinarily, I would respond to this sort of statement with a hearty pfft and move on. But then, even though the podcast episode was published months ago, YouTube fed me two response videos and two people asked me about it in the last week. So it’s on my mind, and I’d like to reflect on how the church should approach this kind of question.

Reference to the Second Commandment makes this an interpretive matter. What is the meaning of the text in our time? More, how do we come to an understanding of the text? Declarations like Baucham’s are persuasive because their appeal to straightforward obedience feels decisive and uncompromising. God says don’t make “images,” so don’t.

Disciples of Jesus know, however, that straightforward obedience to the Ten Commandments misses the point. Jesus’s treatment of the fourth commandment (Sabbath) comes to mind first. (I suppose Baucham would call the Pharisees’ concern about plucking grain or healing on the Sabbath “4CV,” but let me declare a moratorium on that adorable shorthand.) But he also teaches that adultery and murder involve more than we might like to think, honoring parents is about money, and so on. Jesus teaches us to interpret the commandments in light of his message about the kingdom of God. The Christian tradition teaches us to interpret the commandments in light of Jesus himself. A simple appeal to the commandment, however zealous or well-intentioned, won’t suffice.

I recommend four approaches to the evaluation of The Chosen—or any other depiction of Jesus—in relation to the Second Commandment:

Read the Text Closely

Interpret the Text Canonically

Interpret the Text Communally

Appropriate the Text Missionally

(Obviously, these approaches would be equally applicable to any other passage of Scripture.)

1. Read the Second Commandment Closely

Read the whole passage.

If you lift v. 4 from its co-text and attempt to make “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (KJV) into a command about making images as such, then you will miss the information necessary to understand the commandment.

Why does the passage continue “You shall not bow down to them or worship them”? If we obeyed the first part of the commandment, then there wouldn’t be anything to bow down to or worship. A bit redundant, no?

And anyway, what does making likenesses of creation have to do with worship? If my daughter makes an engraving of a tree in art class, that would be a straightforward infringement of v. 4. But then, no one is trying to worship her schoolwork. And that is relevant if you read the rest of the passage.

The point is that simply paying attention to what the passages says will put an abstract understanding of “making images” on shaky footing. We have to consider what the prohibited images and likenesses are for. Clearly, they are for worship. They are idols.

Think through the differences between translations.

The purpose in view is why contemporary translations render the Hebrew word pesel as “idol” rather than the KJV’s generic “graven image.” And it’s why they clarify the syntactical relationship between “graven image” and “likeness of any thing.”

For example, the NRSV has “You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything . . .”

And the CEB has “Do not make an idol for yourself—no form whatsoever—of anything . . .”

Rather than broadly saying, “Don’t make graven images, and don’t make likeness of anything in creation,” the text specifically prohibits the creation of idols—objects of worship—in the form of anything that is not the Creator.

In other words, the commandment is about turning creation into gods—the idolatrous misunderstanding of the difference between Creator and creation. It is not about the representation of God, much less the mere creation of images and likenesses. Getting a handle on the text’s aboutness is vital for interpretation.

2. Interpret the Second Commandment Canonically

Listen to the biblical prophets’ responses to idolatry.

For brevity, I’ll focus on Isaiah’s expression of absolute monotheism:

All who make idols are nothing, and the things they delight in do not profit; their witnesses neither see nor know. And so they will be put to shame. Who would fashion a god or cast an image [Hebrew: pesel] that can do no good? Look, all its devotees shall be put to shame; the artisans too are merely human. Let them all assemble, let them stand up; they shall be terrified, they shall all be put to shame.

The ironsmith fashions it and works it over the coals, shaping it with hammers, and forging it with his strong arm; he becomes hungry and his strength fails, he drinks no water and is faint. The carpenter stretches a line, marks it out with a stylus, fashions it with planes, and marks it with a compass; he makes it in human form, with human beauty, to be set up in a shrine. He cuts down cedars or chooses a holm tree or an oak and lets it grow strong among the trees of the forest. He plants a cedar and the rain nourishes it. Then it can be used as fuel. Part of it he takes and warms himself; he kindles a fire and bakes bread. Then he makes a god and worships it, makes it a carved image [pesel] and bows down before it. Half of it he burns in the fire; over this half he roasts meat, eats it and is satisfied. He also warms himself and says, “Ah, I am warm, I can feel the fire!” The rest of it he makes into a god, his idol [pesel], bows down to it and worships it; he prays to it and says, “Save me, for you are my god!”

They do not know, nor do they comprehend; for their eyes are shut, so that they cannot see, and their minds as well, so that they cannot understand. No one considers, nor is there knowledge or discernment to say, “Half of it I burned in the fire; I also baked bread on its coals, I roasted meat and have eaten. Now shall I make the rest of it an abomination? Shall I fall down before a block of wood?” He feeds on ashes; a deluded mind has led him astray, and he cannot save himself or say, “Is not this thing in my right hand a fraud?” (Isa 44:9–20 NRSV)

In summary, people who make gods of created things are morons.

Reading the Second Commandment alongside Isaiah confirms that what is at stake in the creation of a pesel is not that it is an image but that it is a “god.” The stupidity of breaking the Second Commandment is that created things cannot replace the Creator. Besides God there is no other (Isa 44:6–8).

Let Jesus illuminate the meaning of the text.

The incarnation of the Son of God as the man Jesus of Nazareth clarifies the relationship between Creator and creation. Paul writes:

He is the image [Greek: eikõn] of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. (Col 1:15–17 NRSV; see also 2 Cor 4:4)

This new relationship is expressed in the language of “image” carried forward from the creation of humankind in Genesis:

So God created humankind in his image [Hebrew: tzelem],

in the image [tzelem] of God he created them;

male and female he created them. (Gen 1:27 NRSV)

In the Greek translation of the Old Testament (the Septuagint, abbreviated LXX), the Hebrew word tzelem is translated as eikõn. Humans are the image of God, but this image is defaced by sin. So Paul understands the incarnation of the Son of God to reveal the true image of God in human form, and accordingly, the restoration of human beings to that image:

For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image [eikõn] of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn within a large family. (Rom 8:29)

Just as we have borne the image [eikõn] of the man of dust, we will also bear the image [eikõn] of the man of heaven. (1 Cor 15:49)

And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image [eikõn] from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit. (2 Cor 3:18)

Do not lie to one another, seeing that you have stripped off the old self with its practices and have clothed yourselves with the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge according to the image [eikõn] of its creator. (Col 3:9–10)

So what does this vocabulary have to do with the Second Commandment? Two things. First, pesel and tzelem can both be used to refer to an idol. It’s not as though one is a bad image and the other a good image. They overlap semantically, raising the question of how creation might properly image God. Second, eikõn can likewise refer to an idol. Paul, surely with the Second Commandment and Isaiah in mind, writes:

Claiming to be wise, they became fools; and they exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images [eikõn] resembling a mortal human being or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles. (Rom 1:22–23)

An idol is an unacceptable eikõn—an image of a creature meant to be a god. But every human is meant, as a created being, to be a good eikõn of God. And Jesus, both fully God and fully human, is the eikõn. If the Second Commandment hinges on the distinction between Creator and creation, then the incarnation must inform our understanding of the command. As the eikõn of God, Jesus directs worship to God. As restored eikõnes of God, humans also direct worship to God. Creation can image God. Images, as such, are not the problem. So what about images of these images? Might they also direct worship to God instead of breaking the Second Commandment?

3. Interpret the Second Commandment Communally

Learn from the historical church’s thorough disputation of this issue.

In case you missed it, the Greek work eikõn is transliterated in English as icon. You’ve probably heard the term iconoclast, which in common usage means someone who bucks the system. But in historical theology, iconoclasm refers to the breaking of icons. Because of the Second Commandment, some ancient Christians staunchly opposed the use of Christian iconography. The church was wracked by the iconoclastic controversy for over a century (AD 726–834).

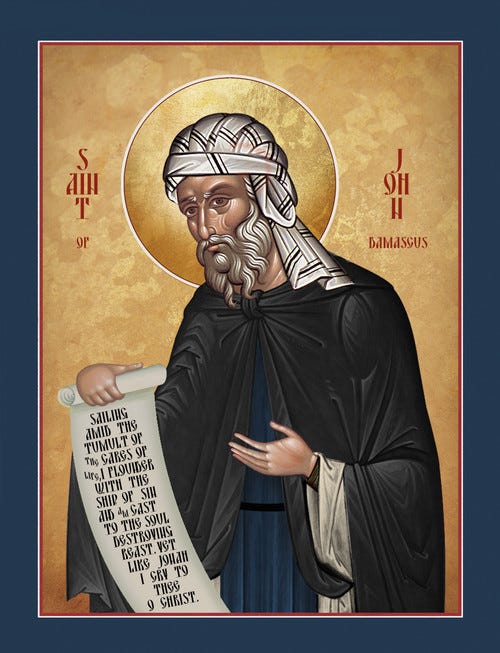

A great deal was said about the question in the span of two lifetimes, but I’ll share just a few excerpts from St. John of Damascus, the leading exponent of the viewpoint that ultimately prevailed and is now considered orthodox.

Let me break up the passage with some topical headings.1

On the Nature of Worship

Worship is the symbol of veneration and of honour. Let us understand that there are different degrees of worship. First of all the worship of latreia, which we show to God, who alone by nature is worthy of worship. Then, for the sake of God who is worshipful by nature, we honour His saints and servants, as Josue and Daniel worshipped an angel, and David His holy places, when he says, ‘Let us go to the place where His feet have stood.’ Again, in His tabernacles, as when all the people of Israel adored in the tent, and standing round the temple in Jerusalem, fixing their gaze upon it from all sides, and worshipping from that day to this, or in the rulers established by Him, as Jacob rendered homage to Esau, his elder brother, and to Pharao, the divinely established ruler. Joseph was worshipped by his brothers. I am aware that worship was based on honour, as in the case of Abraham and the sons of Emmor. Either, then, do away with worship, or receive it altogether according to its proper measure.

On Reading the Second Commandment Canonically

Answer me this question. Is there only one God? You answer, ‘Yes, there is only one Law-giver.’ Why, then, does He command contrary things? The cherubim are not outside of creation; why, then, does He allow cherubim carved by the hand of man to overshadow the mercy-seat? Is it not evident that as it is impossible to make an image of God, who is uncircumscribed and impassible, or of one like to God, creation should not be worshipped as God. He allows the image of the cherubim who are circumscribed, and prostrate in adoration before the divine throne, to be made, and thus prostrate to overshadow the mercy-seat. It was fitting that the image of the heavenly choirs should overshadow the divine mysteries. Would you say that the ark and staff and mercy-seat were not made? Are they not produced by the hand of man? Are they not due to what you call contemptible matter? What was the tabernacle itself? Was it not an image? Was it not a type and a figure? Hence the holy Apostle’s words concerning the observances of the law, ‘Who serve unto the example and shadow of heavenly things.’ As it was answered to Moses, when he was to finish the tabernacle: ‘See’ (He says), ‘that thou make all things according to the pattern which was shown thee on the Mount.’ But the law was not an image. It shrouded the image. In the words of the same Apostle, the law contains the shadow of the goods to come, not the image of those things. For if the law should forbid images, and yet be itself a forerunner of images, what should we say? If the tabernacle was a figure, and the type of a type, why does the law not prohibit image-making? But this is not in the least the case. There is a time for everything.

On the Incarnation

Of old, God the incorporeal and uncircumscribed was never depicted. Now, however, when God is seen clothed in flesh, and conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter, who became matter for my sake, and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out my salvation through matter. I will not cease from honouring that matter which works my salvation. I venerate it, though not as God. How could God be born out of lifeless things? And if God’s body is God by union (καθ’ ὑπόστασιν), it is immutable. The nature of God remains the same as before, the flesh created in time is quickened by a logical and reasoning soul. I honour all matter besides, and venerate it. Through it, filled, as it were, with a divine power and grace, my salvation has come to me. . . .

On the Proper Function of Images

. . . The image is a memorial, just what words are to a listening ear. What a book is to the literate, that an image is to the illiterate. The image speaks to the sight as words to the ear; it brings us understanding. Hence God ordered the ark to be made of imperishable wood, and to be gilded outside and in, and the tablets to be put in it, and the staff and the golden urn containing the manna, for a remembrance of the past and a type of the future. Who can say these were not images and far-sounding heralds? And they did not hang on the walls of the tabernacle; but in sight of all the people who looked towards them, they were brought forward for the worship and adoration of God, who made use of them. It is evident that they were not worshipped for themselves, but that the people were led through them to remember past signs, and to worship the God of wonders. They were images to serve as recollections, not divine, but leading to divine things by divine power.

Even this tiny fraction of the church’s writings on the question demonstrates the need to learn from the tradition instead of acting as though we’re reading and interpreting with autonomy. As members of the church, we never are. The ignorance of treating the depiction of Jesus as an obvious, straightforward Second Commandment violation is embarrassing. The hubris of declaring that position without reference to the tradition is breathtaking.

Ultimately, the seventh and last Ecumenical Council issued this proclamation:

We define that the holy icons, whether in color, mosaic, or some other material, should be exhibited in the holy churches of God, on the sacred vessels and liturgical vestments, on the walls, furnishings, and in houses and along the roads, namely the icons of our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people. Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype. We define also that they should be kissed and that they are an object of veneration and honor (timitiki proskynisis), but not of real worship (latreia), which is reserved for Him Who is the subject of our faith and is proper for the divine nature, ... which is in effect transmitted to the prototype; he who venerates the icon, venerated in it the reality for which it stands.2

Though the dispute continued for some time after this ruling, it remains the orthodox understanding of images in the Great Tradition. Of course, Protestants renewed iconoclasm in many cases, and I too am part of a tradition that gives little credence to the pronouncements of the Ecumenical Councils. Certainly, we have the responsibility to interpret Scripture for ourselves. Just not by ourselves. To disregard the great ecumenical conversation—especially on the handful of issues that came to formal resolution through intense, conflictual theological discernment—would be, to put it bluntly, idiotic.

Address the question as the Body of Christ.

Communal interpretation happens not only historically but also liturgically. The word liturgy is often reserved for the ritualized forms of the worship gathering, with the accent placed on formality. Its range of use is much wider, however, and most broadly it refers to “public service” or, as some like to put it, “the work of the people.” This use places the accent on the public nature of the service. In other words, liturgy is what we do together, as God’s people, in service to God.

My point, therefore, is that the work of interpretation is a part of our liturgy. We should interpret the Second Commandment together, in unison with our worship, prayer, confession, neighbor-care, and all the rest of our life together. Liturgical interpretation shatters the modern illusion that the individual is responsible for determining the meaning of the text for herself.

Interpreting as the Body of Christ is the only way to pull off the approaches that I recommend in this article. You may have been wondering, how can the average Bible reader be expected to perform that kind of careful, theologically informed reading? She can’t. Not as an individual. That’s the point of the diverse members of the Body performing different functions: wisdom and knowledge are given to some, not to all (1 Cor 12:8). Their role in the Body is to serve the other members with those gifts—to offer what others cannot as the Body interprets Scripture. If that seems like a slippery slope to clericalism and hierarchy, well, it can be and has been. And it’s still the way the Body functions! Addressing the perpetual tendency to corrupt the use of spiritual gifts (say, knowledge without love [1 Cor 13:2]) is a separate matter.

This is how we avoid oversimplification and reductionism rooted in individual ignorance: we interpret Scripture together so that our collective knowledge and particular gifts can inform our shared conclusions.

4. Appropriate the Second Commandment Missionally

The article is already long, and I’m prone to go on about missional interpretation, so I’ll be very brief about this final approach.

Does the interpretation by which the church is prohibited from visually representing Christ serve our witness? I know people like Baucham would say that uncompromising obedience to the commandments is our witness. That’s a reasonable position. If only obedience to the commandments didn’t require us to understand them. As it is, the failure of understanding evident in Baucham’s position bears witness to a God who can’t tell the difference between watching a television show and worshiping an idol. Outside observers might respect his religious conviction, but it doesn’t bear witness to God in Christ. Which, incidentally, I think The Chosen is doing quite well.

The passage is from St John Damascene on Holy Images (πρὸς τοὺς διαβάλλοντας τᾶς ἁγίας εἰκόνας). Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption

(κοίμησις), trans. Mary H. Allies (Londing: Thomas Baker, 1898), 13–19, as reproduced by Project Gutenberg. For more info. on John’s understanding of icons, see Nathan A. Jacobs, “John of Damascus and His Defense of Icons,” Christian Research Journal 42, nos. 3–4 (2019): https://www.equip.org/articles/john-of-damascus-and-his-defense-of-icons.

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, “The Seventh Ecumenical Council,” https://www.goarch.org/-/the-seventh-ecumenical-council.