The Intentionality that Faith Entails

On Intentionality [2]

Considering the difference of Brad’s and Richard’s definitions of intentionality from what I have in mind, responding to their statements as though we were talking about the same thing would result in talking past each other. So let me make a general caveat: any time I make reference to their specific statements, “to the extent that we’re referring to the same thing” hangs over every counterclaim.

Still, there is a point of overlap between all three of our perspectives that grounds the conversation and bears on the most interesting tensions. I don’t know how to put my finger on it without considering the technical meaning of intentionality. So I’m going to make the attempt to explain the technical definition, in the hope that Ricoeur is right: explain more in order to understand better.

To begin, Brad avers, “I don’t think popular talk about ‘intentionality’ shares much substantive content with technical theological definitions of the will and intention.” I disagree; the substantive overlap between popular and technical notions of intentionality is exactly where the three of us are having the same conversation as well. To be fair, the technical theological definitions of the will and intention are not strictly synonymous with corresponding philosophical definitions. And in this narrower sense, I still disagree.

Modern philosophical reflection on “intentionality” has a starting point: the Scholastic conception of intentio (Latin) that I presume Brad has in mind. I’ll let the arch-representative, Thomas Aquinas, speak for the technical theological definition: “The will does not ordain, but tends to something according to the order of reason. Consequently this word ‘intention’ indicates an act of the will, presupposing the act whereby the reason orders something to the end.”1 In short, Scholastic intentio is the act of human reason that directs the will toward an end, real (grab that apple) or imagined (go find an apple). There is no “intentionality,” per se, in this discussion except by inference.

Beginning with Franz Brentano in 1874, the referent of intentionality began narrowing to the relationship between consciousness and its objects. In this sense, intentionality is technically the mental states through which your consciousness apprehends everything you are conscious of, including things you are not actively thinking about.

Another technical term is relevant now: attention. Reminiscent of Aquinas’s “tending to,” attention is the philosophical word for the specific mode of awareness (what you’re actively thinking about) directed at a particular intentional object (an object on which your consciousness is operating).

Phenomenologists will have to excuse my quick and dirty explanations. My point is that, to a significant extent, this entire conversation is about a specific mental state (we might more accurately call it attention) operative within the philosophical conception of intentionality. The fact that it is imprecisely called intentionality in popular Christian discourse (which I will continue to do) shouldn’t distract us from the fact that we’re still debating the direction of the will toward an end.

Though faith is not exactly a mental state, I hope it is uncontroversial to say that faith entails the direction of the will toward certain ends and not others. By faith, I don’t mean the even-demons-believe consent to the existence of God or the Lordship of Christ. I mean pistis Christou: trust of and obedience to Christ based on the faithfulness of Christ. And I think it is straightforward to say that faith, therefore, always everywhere entails attention (in the technical sense) to the ends of trust of and obedience to Christ. We do not attain these ends (or others I might list) passively, without attention. Our faith/faithfulness does not merely happen to us. Here I betray my Arminian prejudices. But still, I think Scripture makes this an unavoidable conclusion.

Richard ends his series with a long list of passages that exemplify what he understands to be the biblical “call for intentionality.” Let me reduce this list to a single idea: every single biblical imperative (explicit or implicit) that a believer might obey, if they are not yet habituated to do so, requires intentionality. Not necessarily the version Brad has in mind—”a personal plan of spiritual action,” “daily liturgy,” or “continuous stream of conscious thoughts about following Christ.” But intentionality of some kind nonetheless.

Brad makes a caveat that is critical at this point: “I’m not saying Jesus isn’t calling them (“normies” [read: regular church people], along with “the loser, the mediocre, the motions-going-through-er, the wheels-spinner, the perpetual relapser, the self-loathing, the nominal, the failure”), too, to follow him, to take up their cross like all disciples.” On this we agree fully. But a major part of our disagreement seems to be about what taking up the cross to follow Jesus (discipleship) requires and how possible it is for “normies.”

I’ll leave the possibly of normie intentionality for a later post. For now, what does the cross entail for those who believe? I can’t think of a more comprehensive term for the answer than intentionality. Yet, I don’t think this because of the particular socio-cultural circumstances that Richard has in mind. I agree with him that faith in the secular age evidently requires a greater degree of attention to choices than it once did. But faithfulness always required a high degree of attention to choices, and I’m not sure the differential is as significant as he argues. And ultimately, he’s making two different points, one about the particular importance of intentionality in our context and one about the biblical basis of intentionality.

I’m focused here on the latter, though I would expand my concern to the theological basis of intentionality. Scripture represents how faith might direct the will toward God’s ends: by stating them, writing them, reading them, understanding them, attending to them, and acting toward them. So what does taking up the cross mean? Nothing less. And every bit of this is intentional. I’m not talking about achievement, much less perfection. There is no special status, ability, or gifting in view here. There is only the call that, Brad admits, every normie Christian responds to. That response just is iteratively intentional.

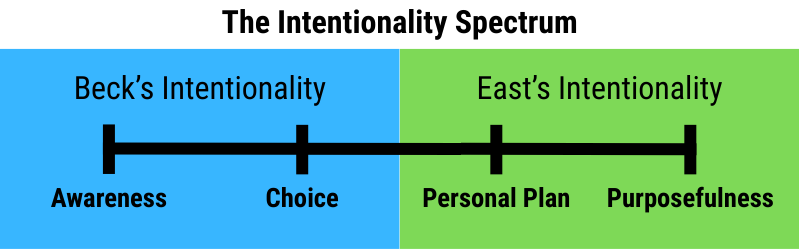

The question of what that intentional response might be is a separate matter. The possibilities lie on a spectrum, call it the intentionality spectrum, that runs from Richard’s awareness and choice to Brad’s personal plan and self-conscious purposefulness.

Behind these possibilities lies another issue, the relationship between practices and virtues in the intentionality discourse. I’ll address both questions in the next post.

The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas, First Part of the Second Part (Prima Secundæ Partis), “Question 12. Intention,” https://www.newadvent.org/summa/2012.htm#:~:text=I%20answer%20that%2C%20Intention%2C%20as,II:9:1.