Intentionality: Practice or Virtue?

On Intentionality [3]

As I said in the previous article, this one is about two distinct questions. I need to start with virtues and practice.

1. What Do Practices Have to Do with Virtues in Intentionality Discourse?

Richard says, “In short, when the habitus of Latin Christendom evaporated we lost our ability to cultivate virtue.”1 For him, intentionality is a substitute, or at least a strategy for compensating. “Intentionality directs the will and virtue stabilizes the will. Virtue doesn’t happen by accident.”2 In other words, intentionality is a practice for cultivating virtue. But which virtue?

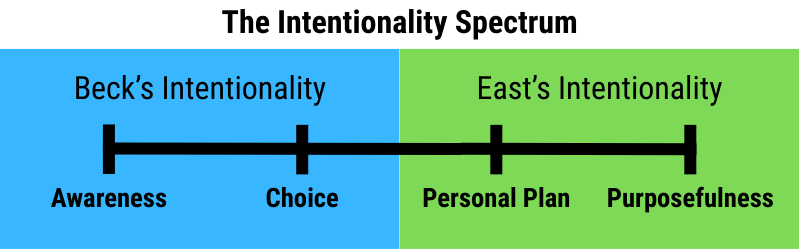

On the one hand, this is Richard’s basic point about our context: absent the habitus of Christendom, it is necessary to “disengage the autopilot”3 of the secular age. So intentionality is the practice of disengaging, and the result is—what? Something like a perception of reality outside the immanent frame (the secular worldview). Let’s call this awareness for the sake of correspondence: on The Intentionality Spectrum, the practice of awareness vultivates the virtue of awareness. Perhaps this is best called a spiritual awareness for clarity.

For reference, here is The Intentionality Spectrum again:

On the other hand, Richard’s list of Bible verses points toward any number of virtues that intentionality might cultivate. “Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you” (Eph 4:31) hints at a decision to obey the command that might result in a peaceful, patient character. “Make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires” (Rom 13:14) suggests a decision to obey the command that might result in temperance. And so on.

The structure is simply iterative conscious choice —> unconscious virtue. Of course, this can be applied to awareness in particular: “Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth” (Colossians 3:2). In Richard’s argument, the list of biblical commands serves to demonstrate the role of choice-intentionality in all of Christian life, thereby establishing the legitimacy of intentionality as such. The central concern is the role of awareness-intentionality in perceiving “things above” in the midst of secularity. Thus, choice-intentionality regarding awareness-intentionality results in awareness-virtue (a habituated disposition to perceive things above, or eyes of faith).

I hope that, although it is not a classical virtue, we might count “awareness” as at least analogous to virtue in view of the paragraphs above. Perhaps not, but I’m going to move on from that presumption to focus on another aspect of the discussion.

Consider Brad’s construal of The Intentionality Discourse’s imagined results:

“always-on ‘intentional’ people”

“a kind of spiritual Navy SEALs—elite, ultra, for the special few”

“urban contemplatives”

There are two things to say about this vision of intentionality. Well, three. First, this is certainly representative of a pathological idea of “maturity.” If intentionality is about that, then let’s boycott the language.

The other two things:

More importantly, Brad is focused on “normie” vs. [whatever is not “normie”] Christianity. Certainly, he does not mean that normal Christians are not aimed at maturity, much less that they cannot become mature (though perhaps that maturity is not normal?). Rather, there is something else that is not normal (for “most people”): leadership. This is the group (“leaders, writers, thinkers”) among which “some intentionality” might be necessary. Historically, the paradigm “elite, ultra, for the special few” is the “contemplative.” (Note the connection between the contemplative life and the cultivation of awareness-virtue.)

But of course, the “normal” church member is neither a church leader nor a contemplative. Is intentionality discourse really trying to put them on those paths? Maybe to the extent that church leadership depends on virtue and that the contemplative’s perspective is related to awareness-virtue. But otherwise, no. I think intentionality is rather about discipleship in the secular age.

Now we come to the crux of the matter. Brad says:

“I’m not saying Jesus isn’t calling them [“normies”], too, to follow him, to take up their cross like all disciples. I’m saying that there is a particular kind of discourse, a way of talking about the gospel and the Christian life, that both reflects and reinforces a specific, local, non-universal sub-group or class of people’s way of being in the world. And it’s not obvious why we should generalize this group’s mode of inhabiting faith to everyone else.”

I’m sympathetic to Brad’s perspective given his construal of what intentionality discourse is aimed at. Again, if he’s right, we agree to a great extent. “Always on” isn’t possible. But that’s true for everyone, not just normies. “A kind of spiritual Navy SEAL” is equally unrealistic. I’ve never met such a person, and I’ve met some pretty spiritual people (and some of them were what I think Brad means by “normie”). “Urban contemplative” is a little more ambiguous. What work is “urban” doing? Are the likes of Comer and company’s readers typically urban, rather than rural? Probably, though I’m not sure why that matters here; I know some pretty intentional rural people. But as I’ve said, the average Christian is certainly not a contemplative, which is a fairly extreme lifestyle. So yeah, if the caricature is representative (and caricatures often are), let’s not go that way.

I think, however, that the real tension here is about what discipleship—for the normie Christian in 2025—means and what it is aimed at. I haven’t talked to Brad or Richard about this claim, so I don’t know what they would say, or whether they would even grant that this is what the conversation is about, but from my perspective, it is.

2. What Does Iteratively Intentional Discipleship (Taking Up the Cross) Look Like Given The Intentionality Spectrum?

To maintain continuity, I’ll put it like this: discipleship is a set of practices aimed at being more “on,” more contemplative, more spiritual. In the theological sense, “perfection” is the goal, and I don’t think we should be coy about that, but stating the goal even that absolutely should not cloud our vision of what discipleship is as a set of practices for all Christians: “teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matt 28:20). What is necessary for learning to obey the teachings of Christ?

I said “iteratively intentional discipleship.” Let me clarify. Discipleship is an iterative practice. We chose to take up the cross daily. We make choices. Some of discipleship—ideally a lot of it—becomes habituated, unconscious, virtuous. But not all of it, not ever as far as I can tell. Christians have to be “on” at least some of the time. Probably a lot of the time if they are not yet highly habituated. In other words, choice-intentionality is especially commendable for those who are not elite, spiritual, or contemplative.

Likewise, practices are necessarily intentional, at one level or another. As Richard points out, you can opt into iterative practices like the liturgy, and even then, “intentionality cannot be avoided.”4 You have to make an intentional choice to engage. But in any case, practices are choices. You either do or do not practice something. The decision this choice entails is inherently intentional. Inheriting a tradition is no exception. As adults, we always decide what to do with our inheritance, familially, communally, and culturally. Some parts of this process remain unconscious. Other parts do not. Tradition and culture are fluid and contested, always.

So what does discipleship look like in relation to The Intentionality Spectrum? At this point, I have to register the opinion that the difference between discipleship and church membership in the secular age is decisive. Brad’s claim that “the local congregation’s got it covered” does not comport with my experience in Churches of Christ. And I doubt that it’s true in high-church traditions, not least because I’ve discipled quite a few former Roman Catholics. I think I’m pretty clear-eyed about what ardent participation in the tradition does.

That said, I’m a big fan of tradition. I love the Great Tradition of Christian faith. I’m conscious of the way tradition functions salubriously in religion and culture. I have advocated the recovery of theological tradition in my tribe. And I have worked to establish tradition on the congregational level. All of this might connect with the practices of discipleship, and none of it is discipleship, per se.

Tradition simply cannot do what discipleship does, and vice versa. Once someone has opted into and engaged tradition, it can work on the level of unintentional formation. Discipleship works on the level of intentional formation. Both are necessary. Our debate comes down to what is sufficient formation for “normie” Christians. I would say no one is exempt from the intentional, iterative practices of discipleship.

And I would say that most church members in 2025, at least in my experience, are profoundly unintentional in this sense. Most Western Christians, to be blunt, have never been discipled. And this is almost always because church membership—liturgical attendance—is presumed to be sufficiently formative. So I tend to be open to authors who are calling for more intentionality. Does every church member need to create a personal plan of spiritual action or personal daily liturgies? No. Are these useful options for many who find mere (regular, lifelong!) membership insufficiently formative? Yes.

Personal plans of spiritual action or daily liturgies are, in other words, a more structured variety of intentional choice. The message should not be that people who make such choices are elite or especially spiritual. In fact, I think such people usually recognise that they are quite the opposite. They need the intentionality because the tradition isn’t doing it.

Still, I want to end with my departure from this vision of “personal” discipleship. One thing tradition does well is communal formation. And discipleship should be communal, too. It is not a solo sport. To the extent that intentionality discourse is individualistic—which seems to be most of the time—I’m against it. In the next and final post in the series, I will specify what I mean by iterative, intentional discipleship. Spoiler alert: its result is the virtue of purposefulness.