The Intentionality of the Missional Church

On Intentionality [4]

In the previous three posts, I’ve attempted to identify (1) the differences between Brad’s and Richard’s representations of intentionality, (2) the extent to which they (and I) are actually talking about the same thing, and (3) how the relationship between virtue and practice clarifies some of the disagreement between us.

In this final post in the series, I’ll put my cards on the table, which is liable to provoke some additional disagreement. In fact, it may locate Richard in the moderate position in the discussion because there are some theological assumptions at work here that, I have reason to believe, Brad and I don’t share. If anyone is wondering why I jumped into the middle of this particular online exchange, the reason is twofold. I really enjoy both Richard and Brad and respect their work immensely. And this discussion happens to tread near the concerns that have occupied my heart and mind for over fifteen years.

Brad ended his post by pointing out that “The Overton Window is not set in stone,” the point being that some of the “contingent conditions” Richard assumes in his cultural analysis need not be taken for granted. In other words, we don’t have to “take secularism for granted.” Brad is not alone in thinking that the response to modern secularization need not be a journey through Ricoeur’s postmodern epistemological desert to a post-critical faith1; it might just be a return to premodernism.

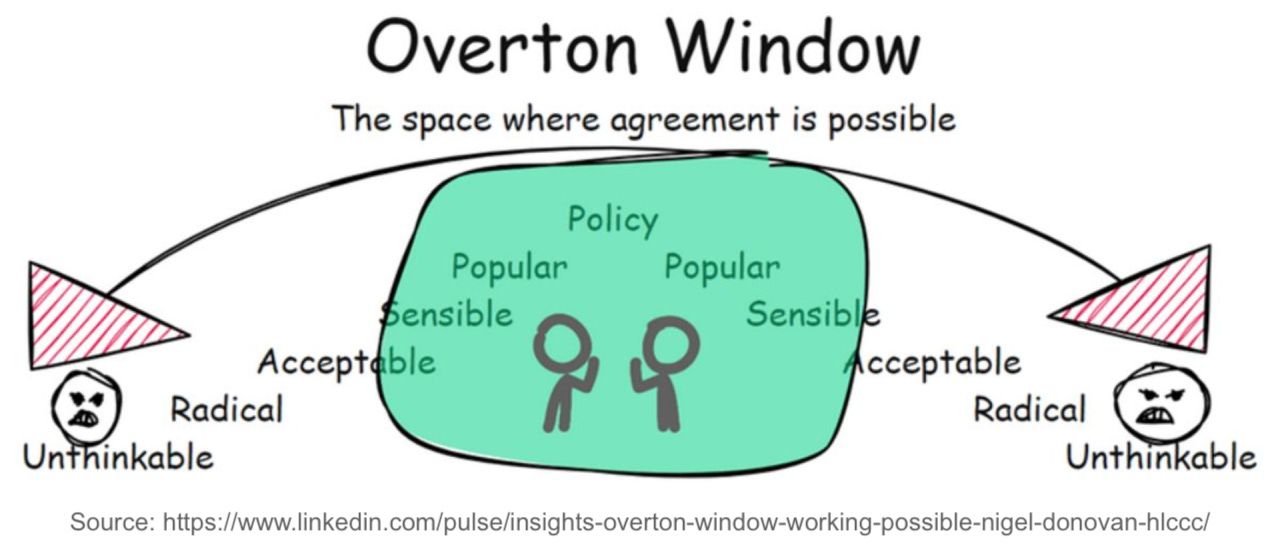

I’m guessing that some of my readers might need a refresher on The Overton Window. The model refers to what is politically possible (basically assuming a two-party system).

Brad is right, the Window is not fixed, because what is popular, sensible, acceptable, radical, or unthinkable changes over time on both ends. Political debate is about shifting the window; policy-making is forced to live in the window.

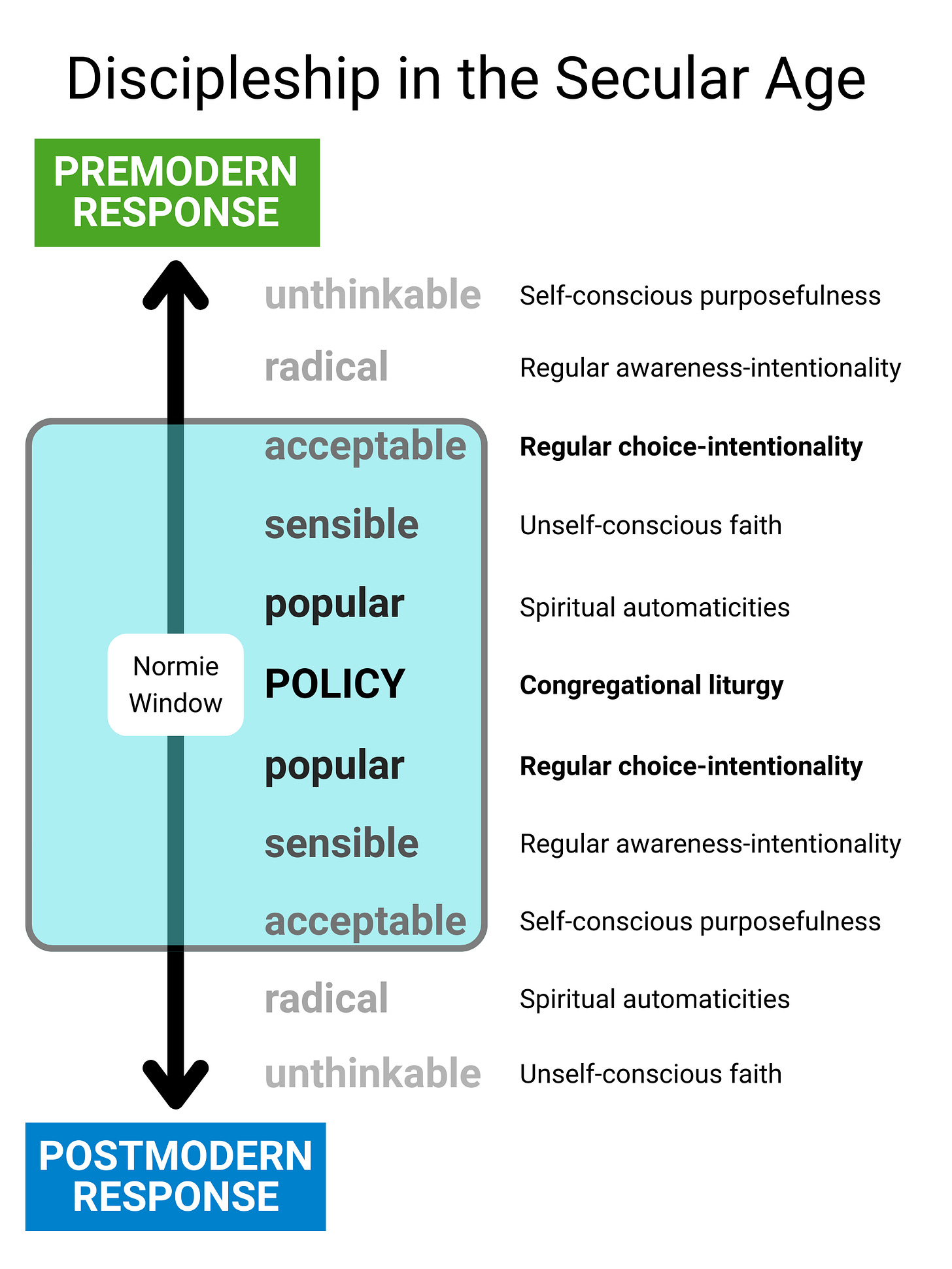

To be clear, Brad is helpfully applying the model to a different domain of agreement/disagreement: the church’s life, specifically which shared vision of the church’s life is possible given divergent assumptions about the “contingent conditions” that determine what is sensible, popular, and agreeable for each side of the debate. Before portraying this continuum, let me put a fine point on what I think is at stake. “The church’s life” refers to Christian discipleship. Which practices of discipleship are necessary in the wake of secularization, and which are conceivable for normie Christians given our contingent conditions? Herein lies the conflict.

I’ve tried to plot the terms of the discussion fairly. It seems to me that the disagreement between Brad and Richard hinges on how feasible it is for normie discipleship to rely on spiritual automaticity (Brad: yes, Richard: no) or to aim for self-conscious purposefulness (Brad: no, Richard: yes). They agree that congregational liturgy is necessary and formative, though Richard insists it requires the same kind of choice-intentionality as other Christian obedience. Brad agrees that “obeying the teachings of Christ, setting one’s heart on the Lord, directing one’s attention to the Spirit” are commendable practices but aren’t what intentionality discourse is on about. Insofar as these practices reflect what I’ve labeled choice-intentionality, we’ve identified the limits of their agreement about normie intentionality.

For Brad, applying this kind of intentionality to awareness (self-consciousness) as such—making awareness-intentionality normal—is radical. Treating self-conscious purposefulness as a kind of virtue is unthinkable for normie disciples. For Richard, relying on Brad’s “spiritual automaticities” in the secular age is radical. Expecting congregational liturgy and minimal choice-intentionality to produce an unself-conscious faith that can survive in the secular age is unthinkable. In the end, Brad is right: what seems unthinkable is a function of assumptions about our contingent conditions. If the premodern conditions of Christendom are still operative, then spiritual automaticities and unself-conscious faith not only suffice but just are the reality of normie Christians. If not, then something more is required.

From my perspective, there is a third dimension to consider: we have to distinguish what is sufficient in our contingent conditions from the reality of normie Christianity. I happen to agree with Richard that the immanent frame is the Western church’s contingent condition, and there is no way through except the desert. The Western church can press on to a second naïveté, but it cannot recover the first naïveté. In the aftermath of Christendom, no few are clinging to that foregone possibility, and understandably so. The mass exodus of Millennials and Gen Z is, in large part, a consequence of that strategy. Why? In a word, the premodern approach is an insufficient witness in the postmodern world. More on which anon.

For now, let’s assume that the premodern approach is a viable pathway. The question remains: Was the reality of normie premodern Christianity a sufficient witness in the premodern world? Just because spiritual automaticities and unself-conscious faith were “normal” doesn’t mean they were the only option, much less the best option. It certainly doesn’t mean they constituted discipleship.

Given the option, I would not see the church return to the ecclesial assumptions of Christendom. I do not grant that the relegation of intentionality to the spiritual “elites” in that arrangement is necessary or good. There are many reasons for my critique of premodern spiritual classism. On the way to a conclusion, I’ll center one. Before the Protestant missions movement (beginning in the eighteenth century), Christian witness was, for a millennium, almost entirely limited to two possibilities: either (1) the passive witness of Christendom’s spiritual automaticities and unself-conscious faith, which amounts to the acculturation of immigrants or conquered peoples, or (2) the mission work of the subset of spiritual elites who set out to bear witness beyond Christendom. There was, in other words, no notion of normies undertaking mission work. Why? Because apart from the passive witness of life within Christendom, witness was an extension of intentionality, and intentionality was for the few, the proud, the clerical (paradigmatically, the Jesuits—who are not, by the way, monastics/contemplatives).

The recovery of the priesthood of all believers was an essential ingredient of the modern missions movement. It became possible to shift the expectation of missionary intentionality to normies—shoemakers, teachers, and physicians. But it was born in the latter days of Christendom, and even among low-church Protestants, the normalcy of the clergy-laity divide persisted well into the late twentieth century. Missionaries were still a special class engaged in a special activity, whose intentionality was not, therefore, characteristic of normies. It wasn’t until the latter half of the twentieth century that a significant theological discourse about the missionary nature of the church emerged among Roman Catholics and Protestants alike. Missional theology is the product (not the origin) of that discourse.

A foundational tenet of missional theology is that the life of the whole church is constituted by participation in God’s mission. Discipleship is missional life together. This claim sets a different standard for “normal” Christianity than merely what is the case most of the time, regardless of one’s contingent conditionals. More, it is a critique of the idea that Christendom represents the way things ought to be for normal Christian life and a rejection of the idea that doubling down on that defunct normal is the solution to the church’s travails in the secular age. In fact, those travails are largely a product of Christendom’s normal. The vast numbers of Christians who have lived or continue to live under the impression that little more than church membership and liturgical participation is “normal” for disciples of Jesus is a symptom, not a prescription. When churches suppose participation in God’s mission is a burden for spiritual elites that normies cannot bear, the intentionality that participation requires is naturally relegated as well. So our vision of discipleship attenuates along with our witness.

At this point, I may have parted ways with Richard and Brad in a variety of ways worthy of further discussion. There are at least two key ideas about which both of them seem to make different assumptions than I do. On the one hand, I’m saying the nature of discipleship is not individualistic. On the other hand, I’m saying the goal of discipleship is not survival.

The Nature of Discipleship

A quote from Brad that I’ve referenced, in part, a few times should be helpful for clarifying my view. He asks, “Is the church the corporate sacrament of salvation, whose liturgy is a foretaste of heaven and whose voice speaks with divine authority? Or is the church the company of disciples, a vanguard of urban contemplatives whose daily life together attests the kingdom of God?” I can’t imagine why these would be mutually exclusive affirmations. But the more interesting point is that “the company of disciples, a vanguard of urban contemplatives whose daily life together attests the kingdom of God” is very nearly exactly what I think the church is—taking into account my previous discussion of “contemplatives.” And it is the only place in the discussion where Brad represents the communal dimension to intentionality that is, in my view, nonnegotiable. Everything else in his portrayal of intentionality discourse is highly individualistic. To the extent that intentionality discourse is individualistic, it’s pathological, and he and I find common ground. To the extent that daily life together bearing witness to the kingdom of God is in view, I’m all in.

And the thing is, while I haven’t read Comer, I have read a lot about intentional discipleship. And a lot of it is about life together. But let me be more personal. I have little patience for personal liturgies or personal rules of life. That’s probably a function mostly of my own foibles and weaknesses, but it’s true. And whenever I have participated in discipling and being discipled, my intentionality discourse has been thoroughly communal. In fact, when I’ve worked on forming a rule of life with discipleship groups, I’ve complained long and loud about the fact that most of the popular resources act as though a rule of life can be personal. To be fair, that’s more a problem of the spiritual disciplines set than the intentionality set, but I suppose they overlap quite a bit and maybe more for Brad than for me.

In any case, maybe a rule of life can be personal. I just think that exercise misses the point of the historical referent (monastic [contemplative?] practices) and proves relatively impotent in comparison with a shared rule of life among disciples committed to life together witnessing to the kingdom of God. My experience, for what it’s worth, is that not only can normie Christians (and I have many real people in mind here, who are “worried about bills to pay and kids to raise and doctors appointments and that weird sound the truck keeps making”) engage in this kind of intentionality but that when they do, it is transformative in ways they didn’t know were possible. Because, of course, they’ve been told their entire lives that showing up for the liturgy and being a member of the tradition were supposed to be enough. But they’re not—not when paying bills and raising kids and going to doctors’ appointments and keeping the car running are weighed in the balance. I do not overstate my experience when I say that, consistently, highly intentional discipleship has proven life-giving for my friends precisely because they needed more than the tradition had given them well into their thirties, forties, and fifties. They need actual discipleship.

As far as I can tell, Richard’s discussion of intentionality is no less individualistic. His discussion is about personal faith, personal deconstruction, and personal reconstruction. If you look back at my first post, the list representing his view of intentionality is thoroughly wrapped up in individual attention, will, and choice. And I guess he would say that is both his interest as a psychologist and an inevitable level of analysis. No doubt, the people who chose to participate in my discipleship groups did so individually (or as couples). Every decision along the way—to engage, to stay, to do life together—is an individual choice. But of course. My point is that what people are intentional about is not a secondary concern. My wife and I have (intentionally) invited church members who have one foot out the church door into our discipleship groups: those who are in the midst of or basically done with deconstruction, even some who have landed on a firmly agnostic conclusion, for the very reason that they were looking for more than the church’s status quo, and they weren’t going to find it in personal practices of intentionality. Granted, some do. It’s possible. And the result of reconstruction through individual intentionality tends to be an individualist faith, not intentional life together bearing witness to the kingdom of God—church membership, not discipleship. Keeping your faith is a victory; it’s not the point of faith.

The Goal of Discipleship

Then what is the point of faith? Richard says something I quite like: “Acts of intention are a participation in the divine life”2 I’m not sure whether he wants to go as far as I do with the implications of that statement, but I’m glad we agree that much at least. Obviously, my “participation in God’s mission” language puts us in the same semantic field. I’ve argued fairly rigorously that missional participation should be understood as participation in the divine life.3 Here’s what I’m getting at: participation in God’s mission is normal for the church, and it requires intentionality, but that intentionality is not about the survival of one’s faith in the secular age. It turns out, that intentionality has the happy effect of securing, reviving, and nourishing one’s faith. But it does so because the most life-giving thing Christians can do is participate in what God is doing beyond themselves, even when the most they can say is “I believe; help me with my unbelief” (Mark 9:24). Even with the most they can say is “We have no more than five loaves and two fish—unless we are to go and buy food for all these people” (Luke 9:13).

There is a kind of spiritual narcissism in the intentionality discourse that I’m happy to jettison. It has nothing to do with becoming a company of disciples whose daily life together attests to the kingdom of God. I begrudge no one personal intentionality if it serves them. Not the deconstructing Christian who needs to practice personal attention to break the immanent frame, not the Christian who benefits from a personal daily liturgy, not the Christian husband who loves his wife but needs help remembering to show daily affection. But discipleship is a communal endeavor, no less than congregational liturgy, no less than the tradition. And discipleship is aimed at the cross, where our life together is broken open for the life of the world, be it premodern or postmodern.

Brad’s critique of intentionality discourse seems equally concerned with survival, not of the normie Christian deconstructing in the contingent conditional of the immanent frame but of the normie Christian overwhelmed with the contingent conditional of modern life. The tradition is, in his view, a lifeline for the regular person who can manage little more than letting faith operate in the background and showing up for the reinforcement of the congregational liturgy.4 I know who he’s talking about; I suspect most of us have been there, even if only for a little while.

My position is simply that while this may be common, it’s not normal: it does not represent the norm of Christian discipleship. If you need to worry about your house, fine; “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” If you need to bury your dead, fine; “Let the dead bury their own dead; but as for you, go and proclaim the kingdom of God.” If you need to tend to your family, fine; “No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God” (Luke 9:57–62). These are hard words. They usually get sidelined with “turn the other cheek” and “sell your possessions” as some kind of hyperbole. Maybe they’re for the spiritual elite. Us normies can’t take that kind of talk literally. Only, that way lies the cross, and at some point, we have to tell the church, the whole church, the truth. Discipleship isn’t personal piety or even personal plans of spiritual formation. It’s not daily quiet time. It’s not church attendance. It is giving your whole life—bills, sickness, kids, and car trouble, along with raises, health, kids again, and leisure—for God’s purposes. And it’s for normie Christians.

God’s purposes. This brings me to my final thought. I mentioned “becoming a company of disciples whose daily life together attests to the kingdom of God.” Becoming is a key word.5 If (!) my adaptation of The Overton Window is accurate, the self-conscious purposefulness of normie Christians is somewhere around “acceptable” for Richard and “unthinkable” for Brad. Maybe the simplest way to plot my viewpoint in relation to theirs is to say that, for me, self-conscious purposefulness is the goal of discipleship. For the missional church, it belongs at the POLICY position. It is the point of congregational liturgy, choice-intentionality, and awareness-intentionality. When spiritual automaticities and unself-conscious faith fail to serve self-conscious purposefulness, they are a problem.

Referring to the previous post, self-conscious purposefulness is a virtue of the missional church—a product of intentionality. In this sense, it is not quite right to put it in the POLICY position. Virtue doesn’t work well as policy, generally. But if the centerpiece of The Overton Window suggests the agenda of the missional church, then make no mistake: liturgy, choice, and awareness, just like spirituality and faith, are means to the ends that the Triune God determines. God’s purposes are definitive, and the church—not just spiritual elites—is called to participate in them, consciously, intentionally, at all cost, without exception.

Ok, three reasons to jump in the middle of this exchange. As my regular readers know, Richard’s reference to Ricoeur sealed the deal. Just remember, Richard brought him up, not me!

By “rigorous,” I mean I can’t recommend my book The Hermeneutics of Participation to normie readers, but, God willing, the readable version will appear in due course.

I’m reminded of something Jordan Peterson said: “Aiming upward toward the divine for one hour a week is a lot more than not doing it ever” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Te3zHucqMPw&t=1s). I have to agree. And that’s not Christian discipleship.

See “What Actually Is a Missional Church?,” https://www.theologyontheway.com/p/what-actually-is-a-missional-church.